Sustainability of Ireland’s Data centres

Data centres use an increasingly greater proportion of Ireland’s electricity and could present an obstacle in achieving emissions targets

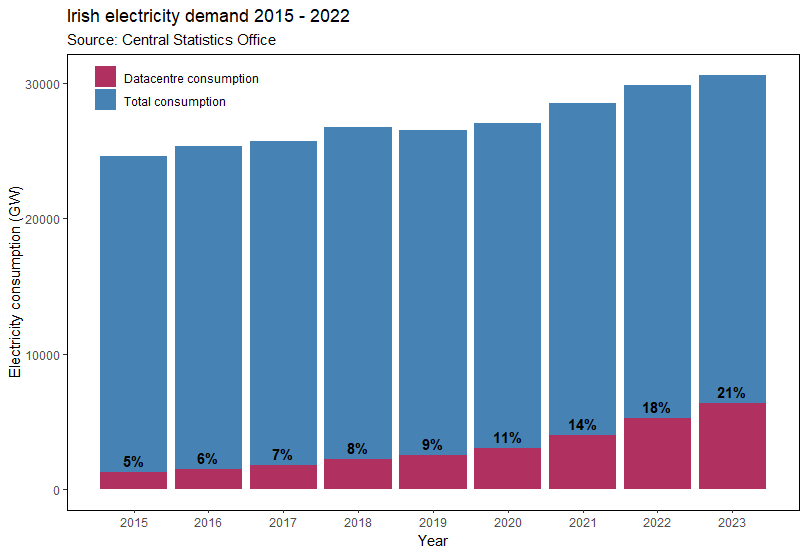

Ireland has benefitted greatly from the technology sector which directly employs 6.4% of the Irish workforce, accounting for 9.6% of Irish wages and 13% of GDP making Ireland. The majority of this comes from foreign-owned companies, the likes of Google, X, Microsoft, etc. Big Tech has seen its energy usage soar in recent years as technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing require a lot of computing power and therefore use a significant amount of energy. In 2023, Ireland’s 80 data centres accounted for 21% of electricity consumption, this was up from just 5% in 2015 - an increase of 412% in 8 years (CSO). In comparison, over that same time, total energy consumption rose by 24% (CSO). The International Energy Agency forecasts that by 2026 datacentres could account for 32% of electricity usage in Ireland (IEA). Importantly, these figures only take into account electricity from the grid: Datacentres have also been using generators to remain operational, emitting roughly as much CO2 as an extra 33,750 cars on the road.

Ireland has an over-reliance on fossil fuels (86% of Ireland’s energy), meaning the vast majority of our energy (82%) is imported. Because of this, Ireland has some of the highest energy prices and one of the higher levels of emissions intensity (CO2 emitted per unit of energy) in the EU. Big Tech companies, aware of the environmental impact of their energy usage, are trying to decarbonise their activity. In September, Microsoft signed a deal to reopen one of the units of the Three Mile Island nuclear power station, the site of the worst nuclear power plant accident in U.S history (Reuters, September 2024). According to the owners of the unit at Three Mile Island which is due to be reopened - Constellation Energy - power from the plant will offset Microsoft’s datacentre electricity use.

Ireland has set legally binding climate targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 51% (compared to 2018 emissions) by 2030. However, the EPA forecasts that we will only achieve a reduction of 29%. According to the Climate Change Advisory Council, the cost of failing to meet our legally binding 2030 EU climate targets could exceed €8 billion. Generating electricity through nuclear fission, like at Three Mile Island, has been banned in Ireland since 1999 so Ireland must use other methods to decarbonise energy usage. In 2023, 40.7% of Ireland’s electricity came from renewable sources, and of this wind accounted for 33.7%. One of the steps to achieving a 51% reduction in emissions is the target of 80% of electricity from renewables set out in the climate action plan. To achieve this the EPA forecasts the need for 10.7 GW installed wind capacity (2023 installed capacity: 4.74 GW) and 8 GW solar PV installed capacity (2023 installed capacity: 0.72 GW)(SEAI).

Given that they make up more than a fifth of Ireland’s electricity demand, data centres present a challenge in achieving emissions targets. However, it should be possible to reduce emissions from electricity generation and existing data centres could also be leveraged to help promote new sustainable energy projects. Corporate power purchase agreements (CPPA) are arrangements between a company and energy provider to purchase renewable electricity through a direct contractual agreement. These contracts are generally long-term (5-15 years) meaning that renewable electricity providers can use the long-term stable income to fund new projects or to secure financing for new projects. The 2019 Climate Action Plan set a target of 15% of renewable electricity demand to be met through these CPPAs by 2030. However, the 2024 plan makes no mention of them, leaving it somewhat unclear as to how CPPAs fit in with reducing Ireland’s dependency on fossil fuels. Local councils at least appear to be considering CPPAs when it comes to planning permission: In 2023 planning permission for a new Google datacentre in Dublin was rejected, with the council citing a lack of engagement with CPPAs as one of the reasons for this.

Other forward-thinking solutions, such as district heating, may also help to improve the sustainability of Ireland’s data centres. Datacentres not only use a lot of electricity but also generate a lot of heat which needs to be vented so that the machinery doesn’t overheat. This excess heat can be delivered through pipes to provide heating and hot water to buildings connected to the system. An Amazon Web Service data centre in West Dublin is supplying heat to a university campus through the first large-scale district heating scheme in Ireland, saving nearly 1,100 tonnes of CO2 in its first year of operation. District heating already supplies most of the heating demand in cities like Stockholm and Copenhagen and has the potential to supply 87% of the heat demand for Dublin by 2050.

Ireland’s planning and legal system does present a significant obstacle to public infrastructure development, as projects can be slowed for years or even halted by appeals, often by individuals not directly affected by the proposed project. However, the Planning and Development Act 2024 was signed into law in October aiming to “...revise the law relating to planning and development; to provide for proper planning and sustainable development in the interests of the common good” which will hopefully accelerate the provision of sustainable infrastructure such as wind and solar farms. With a new Dáil term set to begin soon, achieving climate and environmental goals will continue to be an important issue for the Irish government particularly when potentially faced with billions of euros worth of fines for missing climate targets. Balancing Ireland’s role as a tech hub in Europe with it’s obligations to reduce emissions will be one of many environmental challenges facing the next government. Let’s hope they’re up for the task.